By Frances Vigna via ARTnews: “First we Facebook, then we eat!” instructed artist Elaine Tin Nyo, who, in a culinary class offered by the Museum of Modern Art, embraced René Magritte’s fascination with image-making by reinterpreting the artist’s most iconic paintings as a five-course meal.

Even before I tasted the cocktail based on the artist’s 1930 oil Pink Bells, Tattered Skies—prosecco tinted with sapphire-colored curaçao and mixed with pineapple and lemon juice—I arranged the glasses alongside a plate of rosy-hued cheese puffs, photographed the tableau, and posted it to Instagram with the hash tag #EdibleMagritte.

Cocktails and hors d’oeuvres are based on Magritte’s Pink Bells, Tattered Skies. PHOTO: FRANCES VIGNA.

Working with pieces in “Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926–1938,” Tin Nyo and Lynn Bound, executive chef at Cafe 2, created a meal inspired by the artist’s Surrealist imagery. MoMA hosted Edible Magritte, a class organized by the education department, on November 14th.

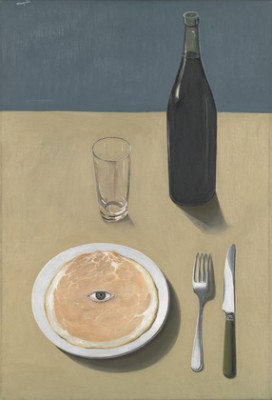

After a tour of MoMA’s Magritte show, guests returned to the café to find prosciutto di Parma and wine organized on tables to resemble The Portrait (1935), complete with an olive standing in for the eye.

The Portrait is translated into prosciutto di Parma with olives and wine. EDIBLE MAGRITTE AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART. PHOTO: PAULA COURT.

Diners were encouraged to photograph their own still life and to indulge in the banality of this traditional image in art history. Tin Nyo explained how the normality of the still life in Magritte’s Portrait contrasts with the indecency of the single eye staring out from the slice of ham.

The main course: A plate of fresh pappardelle—wide, flat pasta—topped with Asiago and arugula salad served with a two-minute egg. Inspired by Elective Affinities, a 1932 painting of a chicken egg trapped in a birdcage, the egg was soft-boiled and placed in its own small bowl. As instructed by Tin Nyo, diners tapped the shell on the table’s edge and scooped out its snowy flesh, breaking the golden yolk over the ribbons of pasta.

The main course consists of pappardelle with Asiago, arugula, and a soft-boiled egg. PHOTO: FRANCES VIGNA.

Dessert: a representation of Magritte’s Celestial Perfections—four canvases from 1930 featuring the artist’s beloved sky motif. Skies came in the form of aquamarine crème anglaise, with pillow-soft poached meringues.

Our instructions were to paint our canvases by pouring the custard onto clean, bare plates, and nestling the clouds into the blue-dyed cream. Magritte placed particular importance on skies, according to Johnson, as they represented another bourgeois artistic cliché.

The first dessert is an interpretation of Celestial Perfections. EDIBLE MAGRITTE AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART. PHOTO: PAULA COURT.

The final plate arrived — the meal’s pièce de résistance was a single, molded dark-chocolate sparrow the size of a baseball. The body had little feet on its underside and a beak sticking out from the head to create a perfect likeness.

The author chomps on her chocolate bird. EDIBLE MAGRITTE AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART. PHOTO: PAULA COURT.

In the 1927 oil Jeune Fille mangeant un oiseau (Le Plaisir), a serene girl violently devours a bird she has plucked from a tree like ripe fruit. I delighted in the macabre reproduction: chomping down on my chocolate bird, hearing the molded body crack like the sound of breaking bones, and tasting the sweet rum-raspberry sauce as it burst from the hollow belly. Ceci n’est pas un oiseau—this is not a bird, I reminded myself as I finished the final dish of the evening—but a piece of chocolate.

Related articles

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

Comments (0)